About the Collection

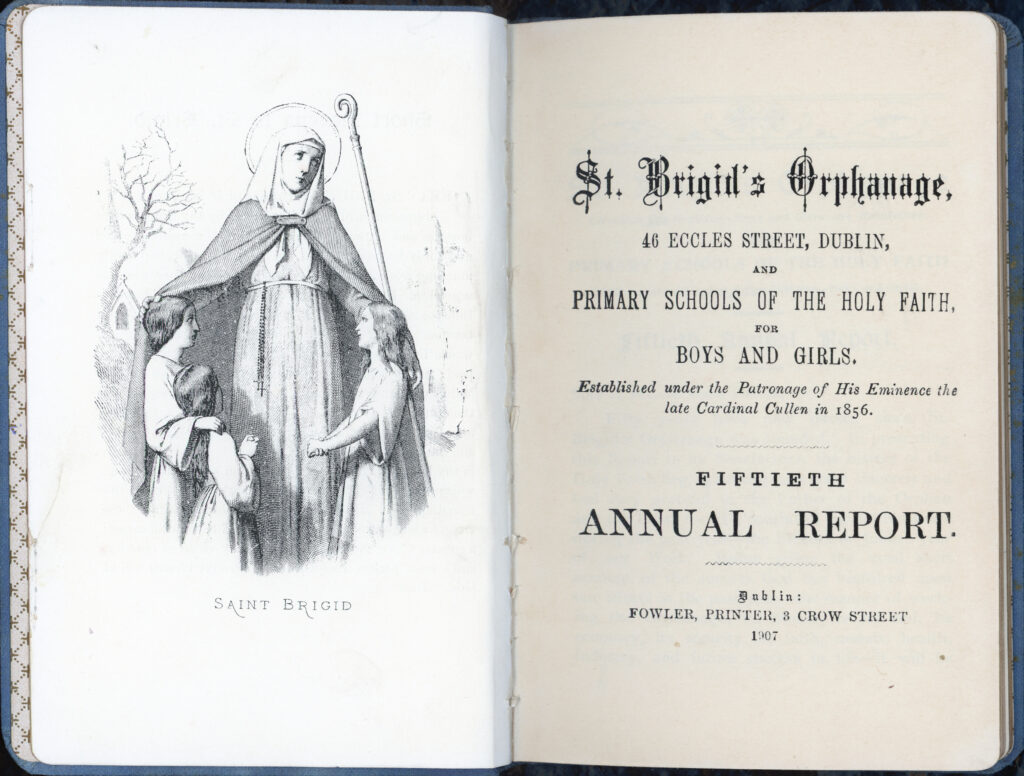

This digital collection consists of a series of fifty Annual Reports of St. Brigid’s Orphanage. Initially, from 1857 to 1860, the reports were delivered as part of the annual reports of the Ladies’ Association of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul. Thereafter the reports are standalone documents. By early 1860, Margaret Aylward, and some other members, decided to focus on a more concerted effort toward St. Brigid’s Orphanage. Although, Jacinta Prunty notes that ‘while Margaret’s active management of this branch of the Ladies of Charity was to span only ten years, she had founded a local association which continued its work for almost 130 years’ (1999, 38). And so, began a new chapter, the full-time devotion to St. Brigid’s Orphanage.

The reports are valuable little-known primary sources for the study of charity networks, poor relief, orphan statistics, childcare, foster care, and education in nineteenth-century Ireland. The political and religious contexts within which they were written – opposition to well-funded English evangelical missions to convert the Irish Catholic poor – makes parts of these reports difficult to handle today. There is certainly very little ecumenism in evidence (Interview with Jacinta Prunty 30, Sept. 2020).

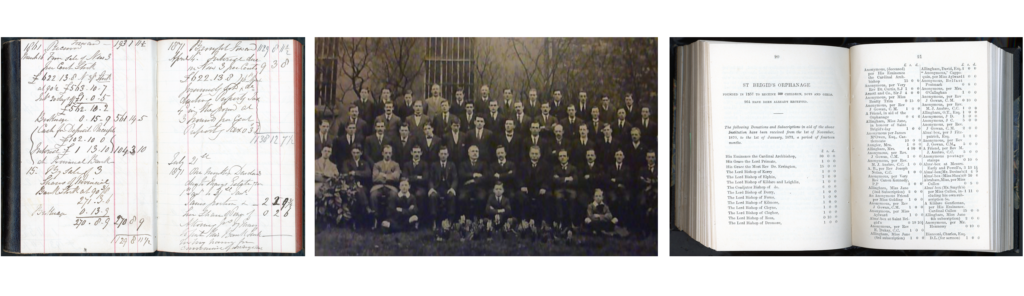

The reports provide an annual update on the mission, philosophy, and objectives of St. Brigid’s Orphanage. Each report provides data on orphan statistics. Here, there were five categories. The mortality rate of orphans, the number who were fostered, entered trades or apprenticeships and those who were reunited with their family. The fifth category were the number of orphans who remained ‘on the books.’

‘St. Brigid’s being a country or home orphanage its success depends principally on the character of the nurse and of the home. The child is morally as well as physically affected by its surroundings. It is then, as we have frequently stated, only in those families where we find evidence of faith, of motherly care and kindness as well as of industry, that we place out children to have their character and habits properly formed….far from tiring of the work, these good women, full of faith and good nature, feel it an honour to be engaged in it, and seem to become more devoted and zealous every day’ ….’The education of the children is simple and limited to what will be useful and practical for them in after life. They are taught well, not only prayers and catechism, but reading, writing, and ciphering. A strict account is kept of their attendance at school, and a substantial premium given for real progress’ (Fiftieth Annual Report of St. Brigid’s Orphanage, 1906).

Aylward’s vision of a boarding-out (foster care) system is encapsulated throughout the reports. Premiums paid to nurses (foster parents) and explanations of how the payment system works is also detailed. The reports also offer insights to the protocols for religious instruction and education. Most reports discuss Proselytism, and some reports provide information about Protestant institutions (orphanages, schools, etc.). The reports often include letters of support, speeches and resolutions, and articles published in the Freeman’s Journal and the Irish Catholic.

Financial accounts were documented annually and describe the support and donations for the cause. The reports detail the generosity of benefactors, and the work of various guilds such as St. Patrick’s, St. Columbkille’s and St. Kevin’s Guild. A list of benefactors is listed in each report.

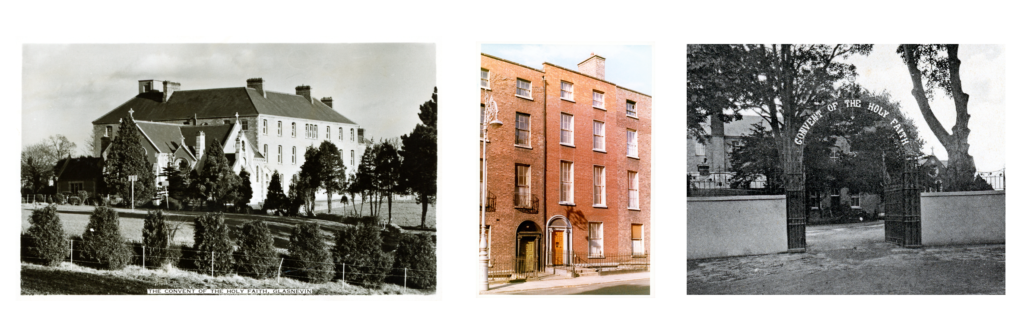

A natural progression from the work of St. Brigid’s Orphanage was the development and expansion of a network of Holy Faith schools. The Annual Reports of St. Brigid’s Orphanage document this advancement from its inception as St. Brigid’s schools (1861) prior to the inauguration of the Congregation of the Sisters of the Holy Faith (1867).

Margaret Aylward’s mission in sponsoring Roman Catholic religious instruction, literacy and numeracy competencies and non-fortuitous character building is evident throughout each report. Beginning in October 1861, under the auspices of St. Brigid’s Orphanage, the first primary school, St Brigid’s Catholic Schools, was opened in 10 Crow Street, Dublin (Temple Bar district). Two years later, the establishment of 14 Grand Strand Street (Dublin) primary schools (north city markets area) occurred.

From 1864-65, Margaret Aylward was operating St. Brigid’s Catholic School of the Seven Dolours, West Park Street, The Coombe and three primary schools in Glasnevin (Dublin). By 1878, Aylward extended her network of schools to Kilcullen (later Celbridge) Co. Kildare and Skerries (North Dublin) in 1884. In Dominick Street, Dublin, she established a convent Secondary and Junior Private school for male and female students; all under the age of twelve. In addition, a series of schools were established in Co. Wicklow (Newtownmountkennedy and Kilcoole).

After Aylward’s death in 1889, the Holy Faith Sisters continued her legacy. By the mid-1890s, a series of schools were established in Finglas, Dublin; all of which were operating under the auspices of the Holy Faith Sisters. The new century witnessed the opening of St. Philomena’s Junior School in The Coombe and the foundation stone was laid with the establishment of St. Mary’s Haddington Road (Dublin) in 1901. By 1903, the Blacklion School in Greystones, Co. Wicklow (primary school) was taken over by the Holy Faith Sisters; with a female-only private day school established three years later. The Holy Faith Sisters resolutely solicited funds for each school; particularly The Coombe (formally Protestant-run Ragged Schools). For example, in the Forty-Eighth Annual Report of St. Brigid’s Orphanage (1905), there are nine pages devoted to school funding. Particular mention is made to Clarendon, Little Strand Street, and Coombe school systems. This solicitation was characteristic of most annual reports. What remained a primary focus was the removal of Irish school-aged children from Protestant schools.

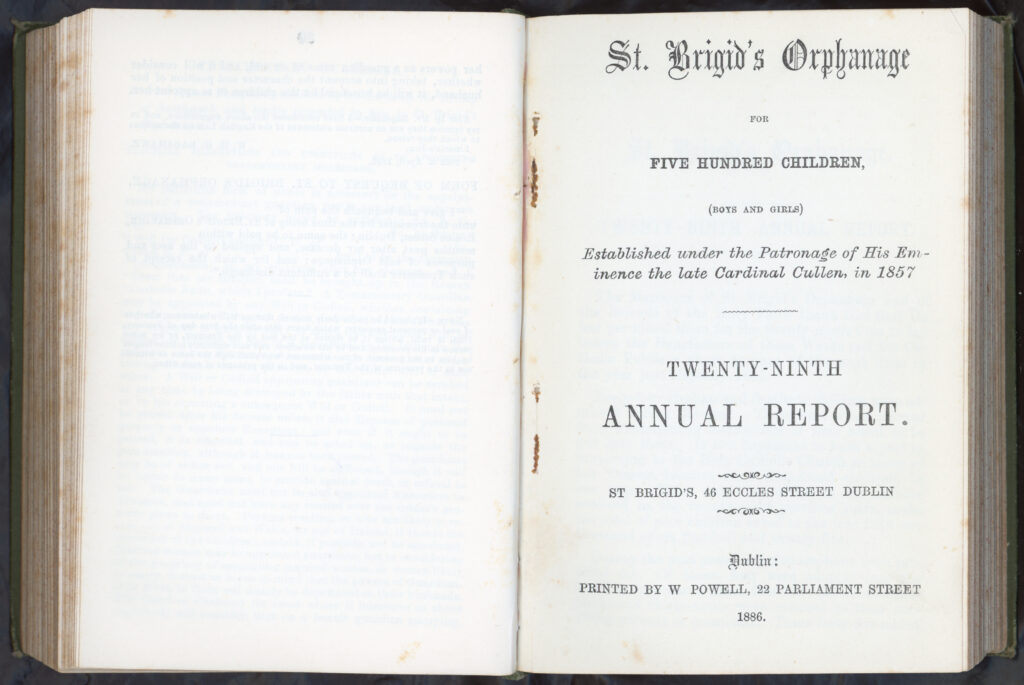

‘The Schools of the Holy Faith were designed not merely to teach and to fit children for the different situations and employment that await them in this life, but above all and before all, to make them steadfast and fervent members of the Catholic Church; that they may the more securely gain the end for which God created them. Now this cannot be freely or fully done in a state-aided school’ (Twenty-Ninth Annual Report of St. Brigid’s Orphanage, 1886).

However, according to Jacinta Prunty, ‘By the 1880s Margaret Aylward’s insistence on remaining outside the system was becoming more difficulty to justify; continuing to go against the grain of popular opinion, and the practice of other religious congregations, is evidence of her deeply-rooted commitment to the principles upon which the schools were opened’ (1999, 107). In 1886, Margaret Aylward encapsulated her responsibility and the importance of education when she reiterated in an annual report:

‘Do not think from this I would like our own humbler classes to be less educated than others. No, I would like them to be superior to other poor in every way and everything, as they are in reality superior to them by the blessing of Faith and the teaching of the one True and only Catholic Church’ (Twenty-Ninth Annual Report of St. Brigid’s Orphanage, 1886).

References

Prunty, Jacinta (1999) Margaret Aylward: Lady of Charity, Sister of Faith 1810-1889, Four Courts Press, Dublin.

Collection Description

La Pina, Helena (2020) ‘Annual Reports of St. Brigid’s Orphanage (1857-1907): About the Collection’, Holy Faith Digital Archive, available: http://hfsdigitalarchive.org/about-the-collections/sbo-annual-reports/

Browse the Collection >>

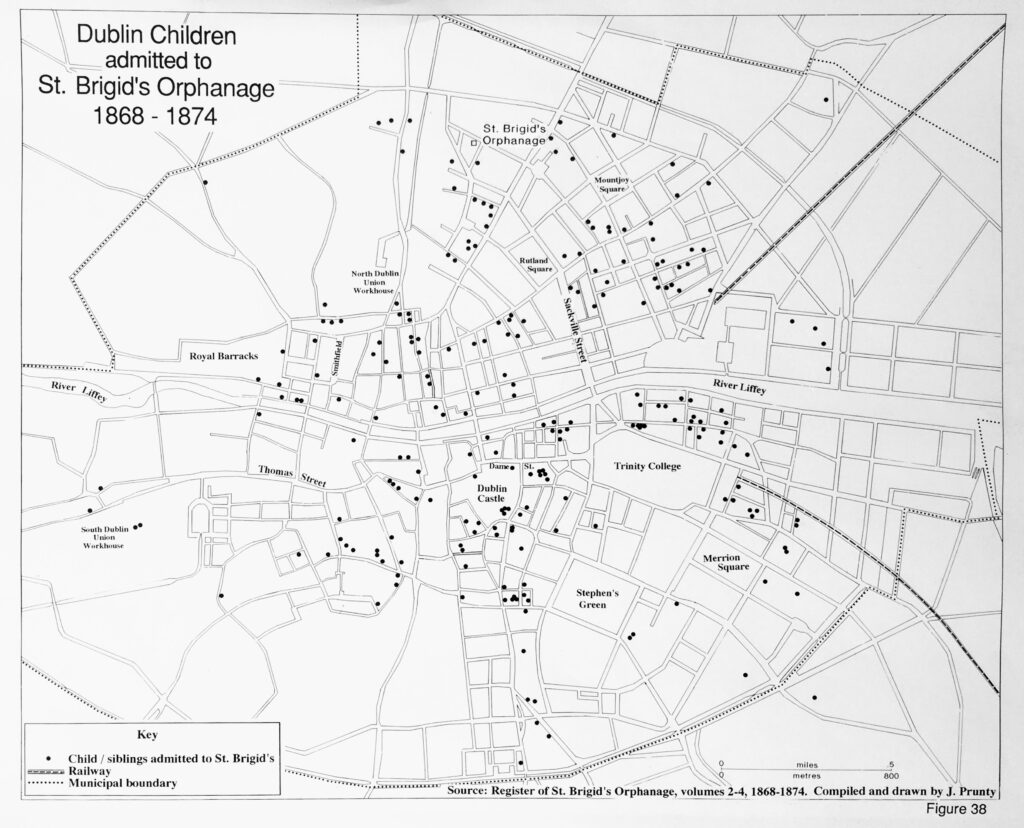

The map was compiled and drawn by Dr Jacinta Prunty, and may be used with the following citation:

Prunty, Jacinta, ‘Dublin Children admitted to St. Brigid’s Orphanage’. Map compiled from the Register of St. Brigid’s Orphanage, volumes 2-4, 1868-1874, available: Holy Faith Sisters Digital Archive, http://hfsdigitalarchive.org/about-the-collections/sbo-annual-reports/